Image Credit: DiBgd, https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Elasm062.jpg

One evening a man and his wife are looking on the internet for a present for their daughter’s birthday. Their daughters has repeatedly (and loudly) stated that the only thing in the world she wants this year is a real unicorn. The doting father looks for the perfect unicorn toy and after hours of searching he finds one advertised as a “one of a kind Siberian Unicorn!” It is very expensive, however the parents assume that it’s a top of the range item, after all nothing is too much for “their princess!” The day arrives, a large lorry pulls into the driveway. “Here’s your Unicorn” the deliveryman states. The ramp moves down, revealing a strange and unexpected sight; a very large, very furry rhino, possessing one very long horn. The parents look on in shock and confusion; this was definitely not the toy they ordered! Their daughter on the other hand has quite the opposite reaction. “I love him!!” She shouts joyfully as she cuddles the creatures’ thick woolly neck. None of her friends have anything like this.

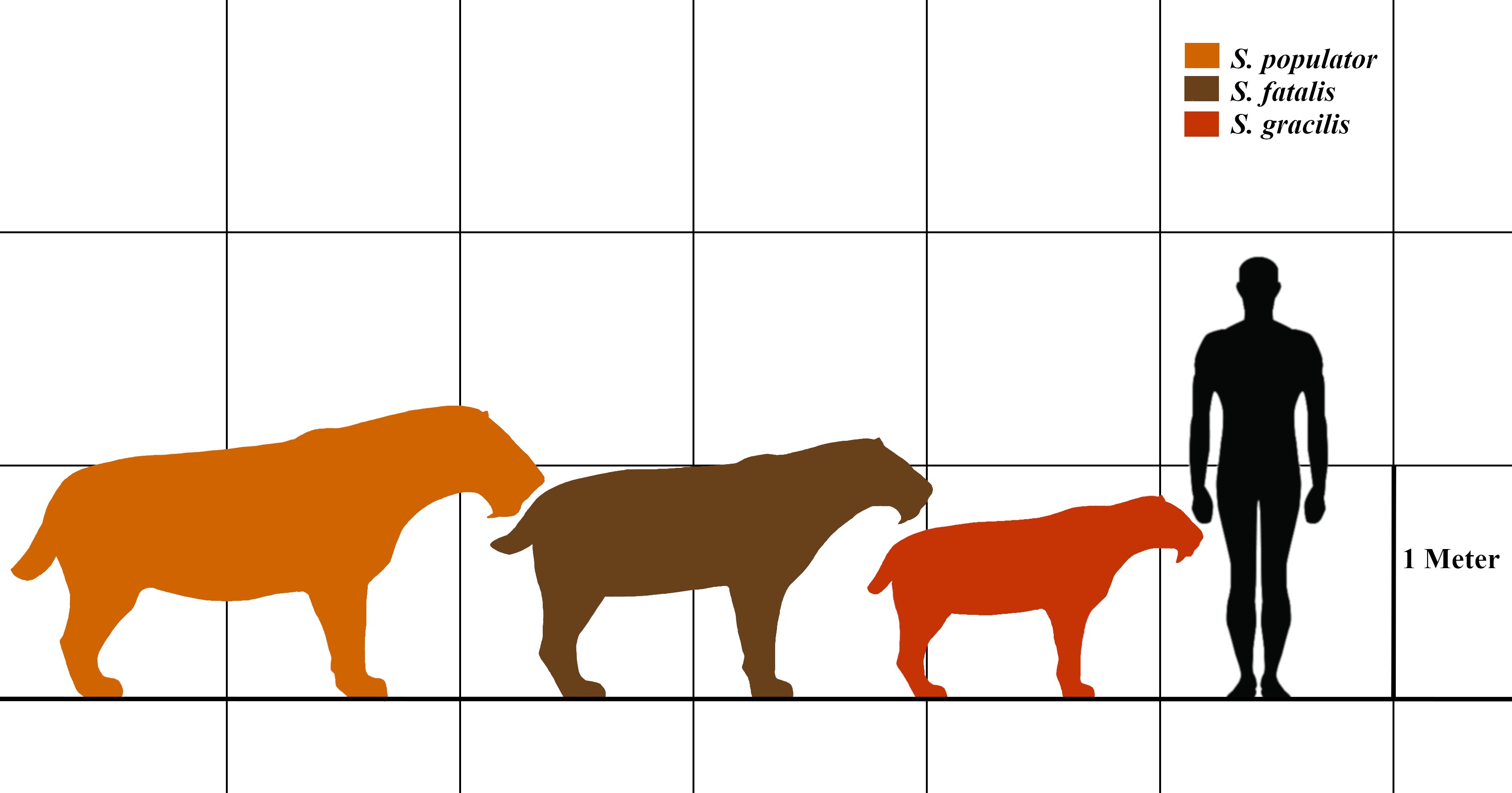

The “unicorn” in this story is named Elasmotherium (meaning “plated beast”). First described in 1808 by Johann von Waldheim, this animal was a big herbivore measuring 5 metres long, 2 metres tall and weighing up to 4 and a half tonnes in the largest species (Elasmotherium caucasicum). Elasmotherium was related to modern day rhinos and a close cousin to the more famous woolly rhino (Coelodonta antiquitatis) that it coexisted with. Like its cousin, Elasmotherium possessed a thick coat of fur to keep warm in the cold of the ice age. This fur traps a layer of heat around the body, giving a layer of effective insulation. In addition Elasmotherium had a thick layer of subcutaneous fat, similar to modern day polar animals. This fat, stored partly in the animals shoulder hump (like bison) would not only keep Elasmotherium warm but would also act as a store of energy for when food was less plentiful. The most striking feature of Elasmotherium of course is its large nasal horn, which could measure longer than a human is tall. It’s thought to have had multiple uses; clearing away snow in order for Elasmotherium to reach its main food source of grass; display against rivals; and defence against predators such as the cave lion. Despite its stocky appearance it is thought that Elasmotherium could run surprisingly fast, useful for charging anything it perceived as a threat.

Image Credit: Ghedo, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elasmotherium_sibiricum_denti_superiori_destri.jpg

Elasmotherium was a widely successful species. Living for around 2 million years its range stretched across Eurasia, from the Ukraine in the west to Siberia in the east. Originally Elasmotherium was thought to have gone extinct around 100,000 years ago. However a study published in 2018, using radiocarbon dating, showed that this animal lived more recently than previously thought, with the new extinction date now being only 39,000 years ago. Around this time modern humans had just reached Europe and Siberia so it is thought that humans could well have come into contact with Elasmotherium. Furthermore it is speculated that this magnificent animal is the original inspiration for the legend of the unicorn. Russian folk tales tell of a great one horned beast, with the body of a bull and head of a horse, known as the Indrik. It is plausible that these stories would’ve spread west into Europe from travellers through word of mouth, evolving over the generations into the story of a one horned horse. There is even a very slight possibility that the Siberian Unicorn could be brought back, or at least a rhino/Elasmotherium hybrid. This is because DNA has been extracted from younger Elasmotherium fossils. Unfortunately, as the DNA is too fragmented to be used for cloning, this is still in the realm of science fiction for now. However this DNA can still give us details on its evolutionary history, showing that Elasmotherium was the last survivor of a lineage that spilt from modern rhinos 43 million years ago.

Image Credit: Altes, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elasmotherium_skeleton,Azov_Museum(1).jpg

So Elasmotherium was a spectacular example of the large megafauna that existed at the end of the last ice age. It also proves, if you believe the speculations, that there really were unicorns. They just were bigger, bulkier and more bad tempered than you might think!

UPDATE! (20/11/2021)

New research conducted by Titov, Baigusheva & Uchytel 2021 has shown that the head of Elasmotherium looked very different to what was once thought! From examination of more complete Elasmotherium skulls they have found that section of the skull beneath where the “horn” was was hollow, and would have supported an extended nasal cavity. This delicate structure was protected by a bony structure with a backwards facing top part. This structure was covered in keratin and gave it a horn that looked (at least to me) a bit like an iron. The extended cavity within would’ve given Elasmotherium an enhanced sense of smell, and it’s suggested that it might have enabled it to increase the volume and range of the sounds it made (calls, grunts etc.). Furthermore, this horn was sexually dimorphic (being larger in males than in females, and therefore probably having display and signalling functions) and still could’ve been used to clear away snowfall to reach succulent grasses that were located using smell!

In short, Elasmotherium didn’t have an almost 2 metre long spear on its head. But an iron shaped, all in one grass detector, snow plough, megaphone and advertising board!

References/Further Reading

• Kosintsev et. al. 2019 paper on the evolutionary history and extinction of Elasmotherium

Kosintsev, P., Mitchell, K.J., Devièse, T. et al. Evolution and extinction of the giant rhinoceros Elasmotherium sibiricum sheds light on late Quaternary megafaunal extinctions. Nat Ecol Evol 3, 31–38 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0722-0

Davis, Josh, “The Siberian unicorn lived at the same time as modern humans”, Natural History Museum, Nov. 26, 2018, nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2018/november/the-siberian-unicorn-lived-at-the-same-time-as-modern-humans.html

Strauss, Bob. “Elasmotherium.” ThoughtCo, Feb. 11, 2020, thoughtco.com/elasmotherium-plated-beast-1093199.