Image Credit: Mariomassone, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dakotaraptor_sketch.jpg

If there was only one place and time that I could take someone new to the topic of dinosaurs, it would undoubtedly be Hell Creek, 65 million years ago. Here, in an environment of lush forests and temperatures similar to Spain today, lived a variety of instantly recognisable dinosaur icons. You could see a Triceratops lumbering through the woods, view a herd of Edmontosaurus browsing the nearby vegetation, hear two Pachycephalosaurus crashing their heads together and ensure to keep us a safe distance from the solid club tail of an Ankylosaurus. To cap it all off you would see the most famous dinosaur of them all, Tyrannosaurus Rex. In one area I could show someone a ceratopsian, a hadrosaur, a pachychephalosaur, an ankylosaur and a tyrannosaur all in one afternoon. Now, thanks to new fossils described only four years ago, you can add a large dromaeosaur (aka, “raptor”) to that list.

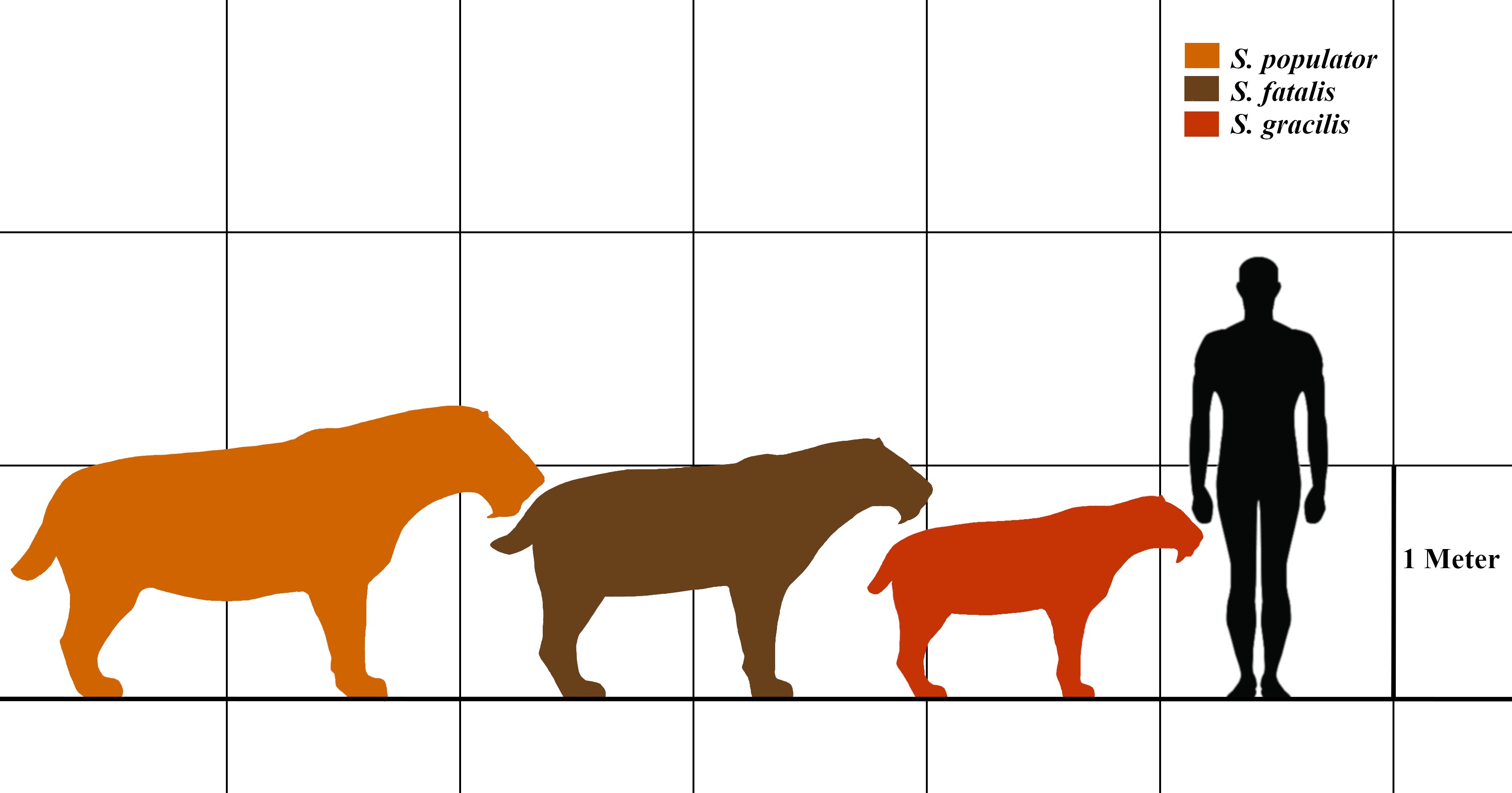

This animal has been given the name Dakotaraptor steini (“Stein’s Dakota Thief”), after the State of Dakota where Hell Creek is located and in honour of palaeontologist Walter Stein. It was discovered by a team led by Robert DaPalma, who described some partially articulated fossilised skeletons of a few individuals including arm and leg bones, some tail vertebrae and teeth. There was also a “wishbone” that was thought to belong to Dakotaraptor, however a study by Arbour et al in 2016 showed that this was actually a turtle bone (an honest mistake on the DePalma and his teams part!) These fossils showed that this dinosaur was no chicken! Measuring 5 and a half metres long and 1.8 metres tall it would have been almost exactly the same size as the famous Velociraptors from the film Jurassic Park. However for a large raptor Dakotaraptor was relatively lightweight, partly due to its vertebrae having air spaces within them. Combing this with legs built for long strides and Dakotaraptor would have been able to achieve top speeds of around 30-40 mph, that’s as fast as a greyhound! Just like the Jurassic Park raptors, Dakotaraptor would have been a lethal predator, hunting in packs to take down large herbivorous dinosaurs. To do this Dakotaraptor needed some serious weaponry, luckily that’s just what it had in the form of the raptors signature weapon; the killing claw on its feet. Dakotaraptor’s was especially big, measuring 9 and a half inches, with a serrated hook shaped end. It used to be thought that raptors used their claw in order to violently slash and disembowel prey. However it is now thought that the claws were mainly used to hold onto large struggling prey and to pin down smaller animals, rather like a modern bird of prey.

Image Credit: PaleoNeolitic, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dakotaraptor_Skeleton_Reconstruction.jpg

The resemblance to birds doesn’t end there. Dakotaraptor, just like all other raptors, was completely covered in feathers (sorry if I’ve just ruined your childhood memories of scaly raptors!). In fact Dakotaraptor is the first large raptor to have direct evidence of feathers (previously it had been inferred that they had them based on smaller relatives possessing them). On its ulna (one of the arm bones) palaeontologists discovered a series of 15 regular notches running along the bone. These notches are called quill knobs and their purpose is to act as anchor points for long pennaceous feathers to attach to. As a result Dakotaraptor would have sported a small pair of wings! However these wings weren’t strong enough for flight (Dakotaraptor was already lethal enough without needing to fly!) Instead, through flapping and balancing motions it could have helped keep the raptor steady while running or holding on to prey. Wing feathers could also have been for display, with potentially bright colours being used to attract a mate or to show off to rivals (a trait common in modern birds). Feathers could have made the animal look bigger and more intimidating and could even be used to cover its young while nesting. With a full head and body of soft feathers, a feathery tail fan and small wings, you might have mistaken Dakotaraptor (and other raptors for that matter) for a giant grounded eagle or hawk from a distance.

Being discovered at Hell Creek also means that Dakotaraptor, just like Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops, was one of the last of the dinosaurs. It would have lived right up until the end of the Cretaceous period and would have been another victim of the asteroid strike on the Gulf of Mexico 65 million years ago. After the impact and resultant climate change the vegetation that its plant eating prey relied on disappeared. With its prey gone Dakotaraptor would disappear too, and with it the entire line of fast, remarkably bird like dinosaurs known as the dromaeosaurs would be no more.

Image Credit: Matthew Martyniuk, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dakota_raptor_scale_mmartyniuk.png

Now I’m going to end this blog with the question that I’m sure some people would be asking. Would Tyrannosaurus Rex and Dakotaraptor have clashed? Such confrontations would have certainly been possible as the two dinosaurs lived in the same place at the same time, and might have hunted similar prey at times. However fights may not actually have been that common. Dakotaraptor would have mostly targeted smaller and faster prey than T-Rex. As a result of this it would have occupied a different role (or “niche”) in the Hell Creek environment, that of a medium sized predator. This idea is called “niche partitioning” and we see it happen today on the African savannah, where cheetahs hunt fast gazelles while lions hunt the larger wildebeest, and so don’t compete with each other (except over a carcass). As a result Dakotaraptor might not have directly competed with Tyrannosaurus Rex for food. But for the sake of fun, what if they had come into conflict? Well a single Dakotaraptor would probably have fared against an adult T-Rex about as well as the Velociraptor at the end of Jurassic Park did! However a pack of Dakotaraptors against an adult, or an adolescent T-Rex would have been a different proposition. One could even envision a Dakotaraptor pack chasing a Tyrannosaurus off a kill in exactly the same way as a pack of Hyenas do to Lions on the African Savannah. So that fight between a T-Rex and a raptor at the end of Jurassic Park could have happened, just with a lot more feathers flying around!

UPDATE: A new study (Frederickson, Engel & Cifelli 2020), published in the journal Palaeonon the 3rd of May 2020, has cast doubt on the theory that raptors like Dakotaraptor lived and hunted in packs. The study examined the level of tooth carbon isotopes in juvenile and adult Deinonychus, a smaller and earlier relative of Dakotaraptor. What they found was the carbon isotope levels were rich in juveniles but depleted in adults. This indicates that they were eating different prey and this difference is consistent with animals like crocodiles who don’t live in packs. In pack hunting animals, such as Lions, both young and adult individuals eat the same food as they’re often sharing a kill between members of the group, so have the same or similar tooth carbon isotope level. In short, raptors like Dakotaraptor May have lived a more solitary life.

References/Further Reading

• A National Geographic article, written by Ed Yong, on the use of the raptors killing claw

Yong, Ed, “Deinonychus and Velociraptor used their killing claws to pin prey, like eagles and hawks”, National Geographic, Dec 14, 2011, nationalgeographic.com/science/phenomena/2011/12/14/deinonychus-and-velociraptor-used-their-killing-claws-to-pin-prey-like-eagles-and-hawks/

• The DePalma et. al. 2015 paper describing the first Dakotaraptor fossils

DePalma, Robert A., Burnham, David A., Martin, Larry D., et. al., The first giant raptor (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae) from the Hell Creek Formation, Paleontological Institute, Paleontological Contributions;14, (2015), https://doi.org/10.17161/paleo.1808.18764

• The Arbour et. al. 2016 paper that pointed out that one of the fossils was actually a turtle

Arbour VM, Zanno LE, Larson DW, Evans DC, Sues H. 2016. The furculae of the dromaeosaurid dinosaur Dakotaraptor steini are trionychid turtle entoplastra. PeerJ 4:e1691 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1691

• Another blog, by Brian Switek, talking about possible interactions between Dakotaraptor and T-Rex

Switek, Brian, “Did Dakotaraptor Really Face Off Against Tyrannosaurus?”, goodreads, Nov. 25, 2015, goodreads.com/author/show/3958757.Brian_Switek/blog?page=23

J.A. Frederickson et al, Ontogenetic dietary shifts in Deinonychus antirrhopus (Theropoda; Dromaeosauridae): Insights into the ecology and social behavior of raptorial dinosaurs through stable isotope analysis, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology (2020). DOI: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.109780