Image Credit: Fred Wierum, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Diplodocus_carnegii.jpg

From February 2018 to October 2021, a giant dinosaur has been travelling the UK. It’s had a long journey! Starting in Dorset, its migrated to Birmingham, then across the Irish sea to Belfast, back across to Glasgow, then south to Newcastle-upon Tyne, on to Cardiff, then to Rochdale and finally to Norwich. After a bit of a delay due to a certain virus millions of times smaller than it, the dinosaur finally reached Norwich in May 2021 and stayed there until the end of October. As Norwich is close to me this humble writer went to visit this dinosaur back in August 2021. I had not seen it since roughly the early 2010s, back when it was a star of one of the most famous museums in the world, the Natural History Museum in London. Since it was already well known, and since dinosaurs are always popular, hundreds of people had gathered to see it. The queue at its temporary home of Norwich Cathedral stretched from the entranceway of the southwest doorway all the way back through the cloisters and snaked its way past the front entrance of the cathedral. It took at least 20 minutes, but finally I reached the front of the line and entered the 900 year old cathedral nave that was big enough to house it! As I entered the huge, vaulted space, Dippy the dinosaur came into view. Dippy predates Norwich Cathedral itself by 153 million years and walked the land that would become the United States. But what was Dippy like? And how did this giant make its way across the Atlantic Ocean to Britain?

The original fossil of Dippy was unearthed in 1899 by railroad workers in Wyoming in the United States. After being fully excavated was put up on display in the Carnegie Museum, Chicago, where it still stands today. Now you might think “hang on, isn’t Dippy in the UK? Not the US!” Well, the UK skeleton we know, and love is not the same as the original fossil that’s at the Carnegie. Instead, it is one of 10 casts (or copies) of those Wyoming bones, (with other casts being present in museums in Paris, Berlin and more). The “Dippy” cast was made and sent to the UK on the order of none other than King Edward VII, who had been shown a drawing of the original skeleton by the owner of the Carnegie Museum, Andrew Carnegie, A Scottish-American Millionaire Philanthropist and Industrialist. Edward VII believed that it would make a fine addition for the Natural History Museum in London. It’s safe to say that he was right, as it has wowed millions upon millions of visitors for 111 years. Originally, Dippy was placed in the museum’s reptile gallery when it was unveiled in 1905. But in 1979 it was moved to its more recognisable position in the centre of Hintze Hall, where it greeted visitors as they entered the museum! In 2017 Dippy was dismantled to be given a deserved rest, being replaced by a hanging skeleton of an even larger animal, a Blue Whale! (Which has affectionately been named “Hope”).

Image Credit: My own (low quality) photo that I took during my visit.

So now that we know how Dippy came to the UK, the next question is what exactly is Dippy? Well, if you were to guess that it was a big dinosaur then you would be correct! More specifically Dippy is a member of the species Diplodocus carnegii, named after Andrew Carnegie himself. Diplodocus means “Double Beam” and it stems from two strange rows of bones on the underside of its tail that helped to support it and promote flexibility. Diplodocus carnegii is not the only Diplodocus species known to science, there are in fact four! (The others being Diplodocus longus, Diplodocus lacustris and Diplodocus hallorum). First discovered in 1878 by the American fossil hunter Othniel Charles Marsh, Diplodocus were long necked, long tailed, heavily built, four-legged plant eaters that belonged to the group of dinosaurs known as the Sauropods. The first Sauropods appeared in the Early Jurassic period (a period lasting from 201-174 million years ago, exactly where Sauropods appeared in this time is still debated), and the group would last up until the very end of the Cretaceous period (66 million years ago). The ancestors of sauropods were small, upright walking, relatively lightweight generalists, a far cry from the giants that would evolve later! Later, multiple sauropod species, including Diplodocus itself, would occupy the large herbivore niche across the world, from the USA, to Argentina, to China and to Australia. The Jurassic was one of the best times for the Sauropods, with many of the most famous species originating in this period. Diplodocus fossils, alongside other famous sauropods such as Brontosaurus, Brachiosaurus and Apatosaurus, are all found in a Late Jurassic rock formation in the United States known as the Morrison Formation. This formation is HUGE! Geographically it stretches across the states of Arizona, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana and New Mexico, while chronologically it contains rock sequences and fossils dating to 155-150 million years ago. As well as Sauropods, the Morrison has preserved many other famous dinosaur species such as Stegosaurus, Allosaurus, Ceratosaurus, Dryosaurus, an early Ankylosaur known as Mymoorapelta and even an early Tyrannosaur called Stokesosaurus, as well as a collection of insects, fish, amphibians, early mammals, other reptiles (e.g. lizards, crocodilians) and flying reptiles known as Pterosaurs. The environment that Dippy and all these other spectacular dinosaurs lived in was warm, seasonal and semi-arid, that progressed to a wetter climate with floodplains and rivers, varying over the thousands to millions of years. Herbaceous (i.e., non-woody plants) were prevalent, with sporadic areas of woodland. This means that Dippy’s world would have had an almost “Savannah” like feel to it (except without any grasslands), with plentiful resources for all the giant dinosaurs. Sauropods are iconic dinosaurs because of their often absurdly huge sizes. They were so big that even a “small” sauropod would usually still be bigger than an Elephant!

Sometimes when you see your old house, city, or a treasured object again after a substantial number of years, it can seem smaller than you remember. Well, this is not what I felt when I saw Dippy again! On the contrary it seemed even bigger! Not only that but now I know more about Paleontology I can appreciate just how unusual Diplodocus is when compared with other sauropod dinosaurs. Here is what I mean.

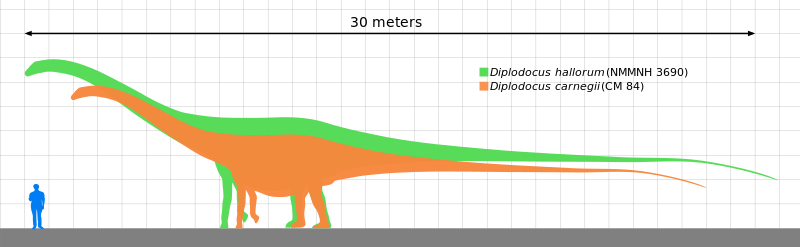

First off, Dippy’s head is small, long and slender compared to the rest of its body, and to other sauropod skulls. Furthermore, this head contains a set of peg-like teeth which jut out slightly at the front, giving it an almost “goofy” look. This skull allowed Diplodocus to grab and strip off (or bite off) the leaves of low and medium growing plants before swallowing them whole. To sustain a Diplodocus carnegii that grew to lengths of roughly 25 metres (and up to 33 metres in Diplodocus hallorum!) and weighed roughly 11-15 tons (or somewhere between 25-50 tons in D.Hallorum), a Diplodocus would’ve needed to spend a lot of time eating. Luckily this “grab and pull” method is efficient, and by swinging their long necks around from side to side they could cover a wide area without needing to waste energy moving around. Furthermore, Diplodocus could lower their necks to access low growing plants, and even (briefly) rear up on their hind legs to access plants that would be out of reach otherwise. This skull and teeth did give Diplodocus a relatively specialized diet, limited to mostly soft leaves, but it meant that it could avoid direct competition with the other huge sauropods that it lived with. These other sauropods ate different plants that grew to different heights. For example, Camarasaurus’ boxy robust skull meant that it could have had a more generalized diet involving tougher woody stems. Furthermore, the orientation and reach of different sauropod necks meant they could access different foods. For example, while Diplodocus had a long, gently S-shaped neck and head that was held at a roughly 60 degree angle to the ground, a Sauropod like Brachiosaurus had a neck held more vertically like a giraffe, which allowed it to reach the leaves of the tallest trees. These differences in diet and head/neck anatomy allowed multiple different species of large 15-30 metre Sauropods to establish functioning populations in the same area at the same time. This is like having at least 5 different populations of animals all at least double the size of an African Elephant crammed into an area the size of Western Europe without the ecosystem collapsing!

Image Credit: KoprX, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Diplodocus_species_size_comparison.svg

Secondly, Dippy had a relatively thin tail, with vertebrae that start off thick at the body end and thinning until they became smaller than your hand. This, along with the “Double Beam” bones mentioned earlier, made its tail strong, but mobile and whip like, very different to the thick and sluggish tails dinosaurs traditionally dragged along after themselves in classic illustrations and movies. Such a tail could’ve had multiple uses. It would’ve counterbalanced Diplodocus’ long neck and potentially been used for communication between other members of its herd (via a recognizable sequence of swings and tail movements). It could’ve also been used as a defense weapon, cracked like a whip or swung into any predators that wouldn’t have been deterred by Diplodocus’ sheer size or strength in numbers. Diplodocus would’ve needed this protection (along with the single row of small spines along it’s back and tail), as the lands of the Morrison Formation was also home to a collection of fearsome threats. Large predators such as the previously named Ceratosaurus (7 metres) and Allosaurus (9 metres), as well as Torvosaurus (10 metres)and Saurophaganax (11.5 metres) would’ve targeted sub-adult, sick or wounded Diplodocus. Also, smaller carnivores such as Stokesosaurus and Ornitholestes would’ve tried to take unwary hatchlings and exposed eggs. Life was tough for a young Diplodocus, but fortunately they didn’t stay small and vulnerable for long. It’s been estimated that, from hatchlings no more than a metre long (that hatched from eggs no bigger than footballs), Diplodocus attained lengths of roughly 3 metres by age 1, 9 metres by age 6, 19 metres by age 12 and the full 25 metres by the age of 20 (though rate of growth and final size attained could vary between different individuals). Just like with humans, Diplodocus kids grew fast and had a growth spurt as teenagers! What fueled this growth was consuming vast quantities of food. It has been found that Diplodocus youngsters had a more generalist diet (i.e., browsing on tree saplings and low growing plants), before transitioning to the more specialized adult diet. This meant they could find food more readily and keep up their fast growth.

All in all, Dippy’s time in the UK has been an unqualified success. The “Dippy on Tour” event alone has been seen by over 2 million people across the country, and the accompanying displays have helped educate people not only about the distant past but also about the current challenges faced by the world today. Not only does Dippy help tell the story of Diplodocus, how it lived, how it ate and the world it inhabited, but it also provides more evidence for why dinosaurs were such successful, remarkable and (yes I’m going to say it!) cool animals!

Further Reading

Prosser, Matthew, “Dippy: this is your life”, Natural History Museum, 1st January, 2016, www.nhm.ac.uk, https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/diplodocus-this-is-your-life.html?gclid=Cj0KCQjws4aKBhDPARIsAIWH0JVsPEwiVHhKSzP_dK7BI-X6s9do5Sklu-ScuPBslgKvrzLzweH0ze8aArY6EALw_wcB

Young, M.T., Rayfield, E.J., Holliday, C.M. et al. Cranial biomechanics of Diplodocus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda): testing hypotheses of feeding behaviour in an extinct megaherbivore. Naturwissenschaften 99, 637–643 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-012-0944-y

Anthony R. Fiorillo (1998) Dental micro wear patterns of the sauropod dinosaurs camarasaurus and diplodocus: Evidence for resource partitioning in the late Jurassic of North America, Historical Biology, 13:1, 1-16, DOI: 10.1080/08912969809386568

• Dunagan & Turner 2004 paper that studied the depositional environment and paleoclimate of the Morrison Formation.

Dunagan, Stan, Turner, Christine, 2004, Regional paleohydrologic and paleoclimatic settings of wetland/lacustrine depositional systems in the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Western Interior, USA, Sedimentary Geology, VL 167, 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2004.01.007

• Parrish, Peterson & Turner 2004 paper on the plant life and climate of the Morrison Formation.

Judith Totman Parrish, Fred Peterson, Christine E Turner, Jurassic “savannah”—plant taphonomy and climate of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic, Western USA), Sedimentary Geology, Volume 167, Issues 3–4, 2004, Pages 137-162, ISSN 0037-0738, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2004.01.004.

Woodruff, D.C., Carr, T.D., Storrs, G.W. et al. The Smallest Diplodocid Skull Reveals Cranial Ontogeny and Growth-Related Dietary Changes in the Largest Dinosaurs. Sci Rep 8, 14341 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32620-x

• A blog article about baby sauropods, the differences between youngsters and adults, and their growth rates

Mike, “Why does a Baby Diplodocus have a Short Neck?”, Everything Dinosaur, December 12th, 2007, www.blog.everythingdinosaur.co.uk, https://blog.everythingdinosaur.co.uk/blog/_archives/2007/12/12/3405222.html

Natural History Museum, “Dippy on Tour: A Natural History Adventure”, Natural History Museum, www.nhm.ac.uk, https://www.nhm.ac.uk/take-part/dippy-on-tour.html

• A blog article by Darren Naish, from 2009, on the biggest sauropods ever.

Naish, Darren, “Biggest… sauropod…. ever (part 1)”, scienceblogs, December 28th, 2009, https://scienceblogs.com/tetrapodzoology/2009/12/28/biggest-sauropod-ever-part-i